|

|||||||

Flag of Bhutan |

|||||||

|

A small, beautiful, wonderland high in the Himalayan Mountains, Bhutan is located between China and India. It is landlocked and had little interaction with other cultures. Since 1907 the country has been ruled by a king. People led simple lives, growing animals and crops for their survival. The people loved their king and country. While people in Bhutan were leading their agrarian and peaceful lives, the king was creating a new concept that came to be known as Gross National Happiness. |

|||||||

Bhutan countryside |

Taktshang monastery |

Bhutan's mountains are "close to heaven" |

|||||

|

Kamenev, writing in BusinessWeek.com in October 2006, ranked Bhutan as the eighth happiest country in the world. Bhutan measures it's happiness through an idea called Gross National Happiness (GNH). It uses this concept instead of Gross National Product (GNP). The reason for this is to emphasize happiness rather than financial success. The idea of GNH was first thought of by King Jigme Khesar Nagyel in the 1970's. Helliwell, Layard, and Sachs, stated that GNH is a better way of measuring country happiness than GNP (World Happiness Report, columbia.edu. The Earth Institute, Columbia University, n.d.). "Gross National Happiness (GNH) measures the quality of a country in a more holistic way [than GNP] and states that the beneficial development of human society takes place when material and spiritual development occurs side by side to complement and reinforce each other" (pg 111) . GNH uses 33 indictors clustered into nine domains. The domains are "psychological well being, time use, community vitality, cultural diversity, ecological resilience, living standard, health, education, good governances" (pg 109).

|

|||||||

|

GNH uses a very complicated definition with formulas that add even more complexity to it. There seems to be a disconnect between GNH and happiness in the life of an individual. Gross National Happiness was the constitutional monarchy's policy, and it came at a great human price paid by over 105,000 exiled Lhotsampa (southern Nepalese descent people) Bhutanese citizens who were subjected to ethnic discrimination.

|

|||||||

|

Before the exile, visitors to Bhutan would see people living unfortunate and poor lives, even while those living there were reported to be content with their lives. For instance, Rizal, a Bhutanese human rights activist who spent eight years in prison in Bhutan, wrote about the country and his experiences as a citizen and as an officer of the monarchy. His most famous book was Torture Killing Me Softly in which he wrote about life before the exile saying, "The country was very backward. There was utter lack of sanitation. People urinated in open areas and spitted chewed beetle leaves here and there." While, describing the poor and unsanitary conditions in which people lived, he said that they "seemed jolly and amiable" in their everyday lives (pg 17-18).

|

An agrarian existence |

||||||

|

The increasing population and growing political awareness of the Lhotsampa people caused the monarchy to impose unjust restrictions on their lives. Despot wrote that in the 1980's and 1990's "The growing ethnic Nepali population was seen as a threat by the Bhutanese elites, and discriminatory laws were put in place that robbed them of their citizenship" (pr 2). Even though my parents and grandparents rarely talked about Bhutan, when I asked my dad about why he and the other Lhotsampas were exiled, he told me that the reason the southern Bhutanese were exiled was that they were growing in number and political influence and they were becoming a threat to the monarchy's political majority. He also said that when the Lhotsampa people started settling in Bhutan over 100 years ago, they kept their own culture, religion, and language.

|

|||||||

|

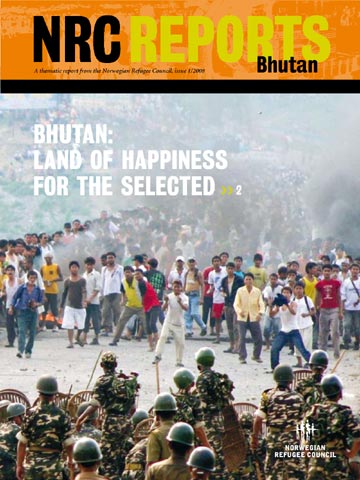

A rmy confronts unarmed citizens |

In the early days of

exile, my grandfather was

selected by the Bhutan

monarchy to be

a village leader.

However, his belief in and support of democratic ideals brought

the attention of the authorities.

This attention frightened him, and he left the country for fear

of his life. The police

came looking for him and beat my great grandmother because she would

not tell them where her son had gone.

Soon after that, the rest of the family fled in the middle of the

night to India. Another

refugee, Hari Acharya, wrote in a blog "how his father was hung upside

down and beaten for not being obedient to the compassionate King" (pr

1). He also mentions that

tortures and rapes went on in the name of the democratic monarchy.

All of these actions by the monarchy caused the Lhosampa people

to flee the country.

|

||||||

|

|

|||||||

|

The monarchy had many cruel and aggressive ways to force people out of Bhutan. At first it imposed laws that forced a new culture on the Lhotsampa people. Then they threatened the Lhotsampa by sending police and army officers to tell them to leave. After that they started burning houses. They stole property papers and they forged people's names on legal documents. In an interview with Dr. Naresh Subba, one of the earliest Bhutanese refugees to come to the United States, he said that he was returning to his home in the south after completing a Bachelors degree at the only college in the country. It was located in Kanglung, Bhutan, which was a two-day journey by bus plus another day by foot. Upon reaching home he found that his family had left taking only personal essentials that they could carry. They were forced to sign a document saying that they had left willingly. When he looked at the document he saw that someone had also forged his name on the document testifying that he, too, had "voluntarily" left the country. When he raised the issue with the police they told him that he would face serious consequences if he stayed in Bhutan. He left and was reunited later with his family in a refugee camp in Nepal.

|

|||||||

|

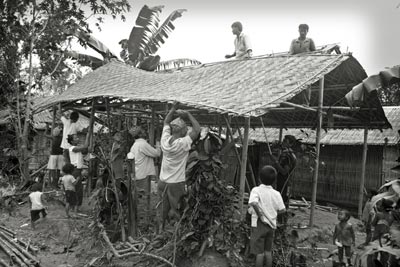

With jobs and citizenship taken from them, the Bhutanese refugees lived in bamboo huts without running water and electricity for 18 years while the governments of Nepal and Bhutan argued that they were not responsible for the refugees. Finally the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees worked out a resettlement solution to six different countries. After the "constitutional" monarchy and the "benevolent" King stole their property, their animals, and their livelihoods, the people fled with nothing.

|

This bamboo and thatch hut was home to 8 or more people |

Only by the humanitarian efforts of the United Nations were the exiles provided huts and rations to exist. While there, former citizens lived in huts and King Jigme Singye Wangchuk and Prime Minister Jigme Yoser Thinley promoted Bhutan as a happy nation while hypocritically ignoring the citizens they exiled. While they were deceiving the world about happiness in Bhutan more than 105,000 former Bhutan citizens were paying the price of Bhutan's Gross National Happiness. | |||||

|

Thapa wrote an article titled the "Bhutan Hoax: Of Gross National Happiness" in which he described Bhutan's "democratic monarchy" as systematically trying to erase all memory and records of the Lhotsampa exiles. The monarchy destroyed property records and changed the names of villages. They employed agents to write and deny the statements written on blogs and websites by refugees expressing their losses and torture. Moreover, the monarchies of Nepal and Bhutan engaged in 18 years of dishonest negotiations as the refugees sought and hoped for repatriation (pr 6). |

|||||||

Wealthy people wearing ghos engaged in the national sport of archery |

Coronaton of king attended by wealthy people |

King's palace |

|||||

People shop at a bazaar in Bhutan |

Jugs lined up awaiting water in refugee camp |

Refugee huts made out of bamboo and thatch caught on fire frequently |

|||||

|

GNH is a fascinating concept that has caught the imagination and attention of today's major economic and political thinkers to the extent that Bhutan Prime Minister Thinley was invited to address this topic at the United Nations in New York in 2011. While the GNH concept has taken on an intellectual life around the world, personal happiness in the lives of people in Bhutan exists only because of the ignorance of its people and the fear they have of their monarchy. Gross National Happiness works for the monarchy, but it came at a great price for many of Bhutan's citizens.

|

|||||||

|

Works Cited: Acharya, Hari. Rev. of So Close to Heaven: The Vanishing Buddhist Kingdoms of the Himalayas, author. Barbara Crossette. Amazon.com 16 Dec1999. Web. 24 March 2013. Despot, Maja. "The Dark Side of the 'Happiest Country in the World.'" Elephantjournal.com. 21 Oct 2012. Web. 1 April 2013. Ghimirey, Durga. Personal interview. 23 March 2013. Helliwell, John, Layard, Richard, Sachs, Jeffrey. "World Happiness Report." columbia.edu. The Earth Institute, Columbia University, n.d. Web. 24 March 2013. Kamenev, "Marina World's Happiest Countries." Businessweek.com. BusinessWeek. 11 Oct. 2006. Web. 24 March 2013. PhotoVoice and the Bhutanese Refugee Support Group. “Bhutanese Refugees: The Story of a Forgotten People.” Bhutaneserefugees.com. PhotoVoice and the Bhutanese Refugee Support Group. n.d. Web. 1 April 2013. Rizal, Tek Nath. "Torture Killing Me Softly: Bhutan through the Eyes of Mind Control Victim." bhutanmediasociety.com. HRWF & GRINSO. 2009. Web. 23 March 2013. South Asia Terrorism Portal. "Timeline Bhutan Years - 1907-1999." satp.org. Institute For Conflict Management. 2001. Web. 24 March 2013. Subba, Naresh. Personal interview. 21 Oct. 2012. Thapa, Saurav J. "Bhutan Hoax: Of Gross National Happiness." fletcher.tufts.edu. Wave Magazine, Tufts Fletcher School, Tufts University. 13 July 2011. Web. 1 April 2013. |

|||||||

|

Note: This article was written by Nirmala (Nilam)

Ghimirey

for her freshman English class (11002) at Kent State University in

April of 2013. Ms. Aldergate was her instructor. |

|||||||

| Opinion Page | |||||||

|

Home |

|||||||